HAPPY NATIVITY TO ALL FRIENDS, FOLLOWERS & READERS OF THIS BLOG!

Happy Nativity, according to the Coptic calendar that follows the Julian calendar, and hence the Nativity for the Copts, and many other Eastern and Oriental Christians, falls on the 7th January and not the 25th of December.

Coptic Nativity is a two day celebration: the first day of Nativity is the 6th of January while the second day is the 7th of January. Prayers for Coptic Nativity are conducted in the evening of the 6th.

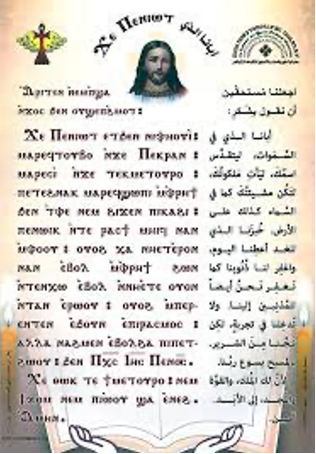

In Coptic Christmas is not used – it is a late introduction in Western Churches anyway. The Copts call the day, The Birth (ing) of Jesus Christ as you can see from the script on the icon.

The greeting is: “Christ is born!” And the response is, “Indeed He’s born!” The emphasis is on the fact that the little child born on this day is not simply Baby Jesus, but the Christ himself who has been prophesied to come – it is the birth of the Saviour of the World from sins.

Christ is born!

PROFESSOR PHIL BOOTH AND HIS WRITINGS ON THE CHRONICLE OF JOHN OF NIKIU

Professor Phil Booth is A. G. Leventis Associate Professor in Eastern Christianity, St Peter’s College, Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Oxford. He is interested in ecclesiastical history, in particularly the history of eastern Christianity in the eastern Roman empire. This has naturally made him come to face with the Copts and their history in that period. He has written extensively. Recently he joined the Universität Hamburg’s project to produce a critical edition of the Chronicle of John of Nikiu, thereby joining Dr. Daria Elagina.

Three of his important papers/chapters in books are:

The Muslim Conquest of Egypt Reconsidered

The Last Years of Cyrus, Patriarch of Alexandria (†642)

Shades of Blues and Greens in the Chronicle of John of Nikiou

On 29 July 2019, Daria Elagina, a research fellow at Hiob Ludolf Centre for Ethiopian Studies, Universität Hamburg, defended with success her PhD dissertation in Ethiopian Studies: The Textual Tradition of the Chronicle of John of Nikiu: Towards the Critical Edition of the Ethiopian Version.[i]

And now Elagina seems to be delivering on her intention. Recently she has divulged the excellent news (see here) that a new project, funded by the German Research Foundation, has been dedicated to the critical edition of the Chronicle of John of Nikiu. Dr Elagina is the principal investigator of the project. Phil Booth, Professor in Eastern Christianity, University of Oxford, who has published excellent articles on the Chronicle, has accepted to join the project. The project will extend from 2022 to 2024 and will be hosted by Universität Hamburg.

The project aims to produce a new text-critical edition of the Chronicle. It will produce a printed edition, a digital edition, and a new English translation. The only complete edition of the Chronicle until now has been that of Hermann Zotenberg. It was published in 1883, with a French translation. Robert H. Charles, in 1916, published an English translation based on the same manuscripts Zotenberg depended upon. Zotenberg’s edition unfortunately has several defects, including muddling of proper names of individuals and places, missing chapters, confused chapter ordering and arrangement, and inaccurate assignment of rubric to chapter. Zotenberg and Charles relied on two direct witnesses, both Ethiopian: the first one is BnF Éth.123 (No. 146 in Zotenberg’s Catalogue), kept at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris; and the second one is Orient 818 at the British Library in London. Probably only BnF Éth.123 was available to Zotenberg.

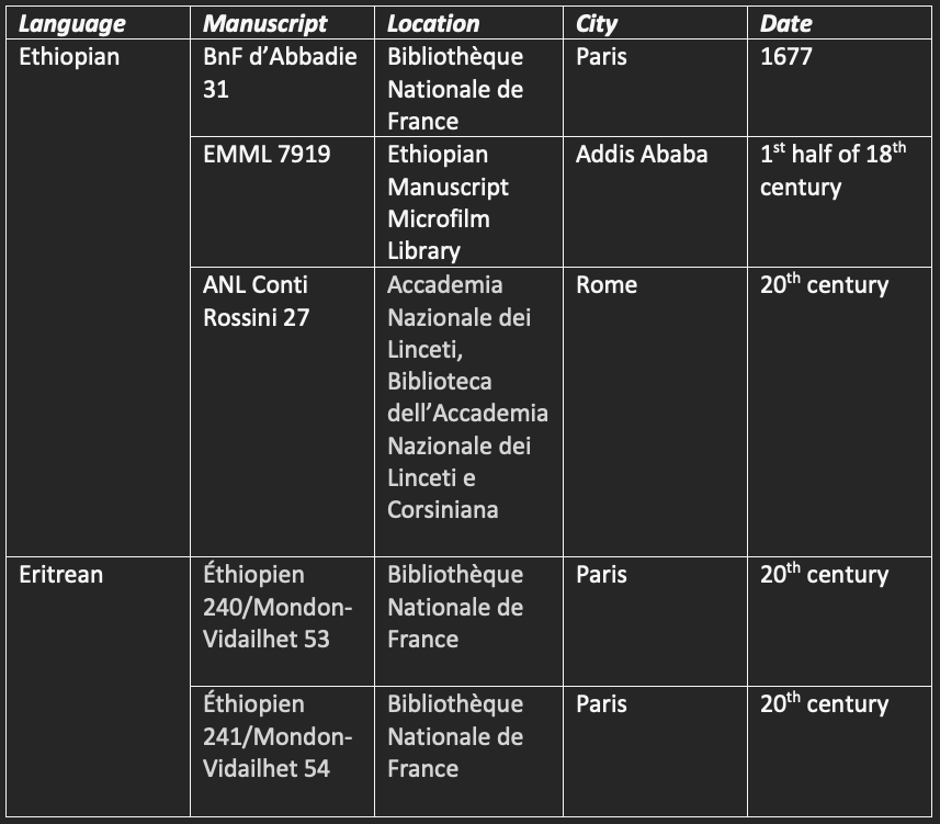

Today, however, we have seven direct witnesses[ii] : the two above plus five others, three Ethiopian and two Amharic (see table below). Not all are the same, and it is hoped that when they are studied all, they will help the researchers to reconstruct an accurate text as it appeared in its original.

In her PhD dissertation, Elagina, worked on five direct witnesses, all Ethiopian and none Eritrean. The project’s edition will rely, she tells us, on at least five direct witnesses. In a footnote, she lists the five Ethiopian witnesses and none of the Eritrean two. I just hope that all available witnesses will be looked into and used.

This is a project that many have been praying for. The Chronicle, as Elagina says, has for years been a scholarly desideratum. Many will welcome it because it is an essential source for historians dealing with Late Antiquity. The Copts will wait with patience for its completion because of the importance of the last twelve chapters (from Ch. CX to Ch. CXXI) of the Chronicle in writing the history of the Arab Conquest of Egypt and the Coptic reaction to it. The national importance of this Chronicle cannot be over exaggerated.

We must all thank Dr Elagina for this project. Without her it probably would not have seen the light.

[i] I have written about this before, and the reader can access my article here. Dr Elagina’s dissertation abstract was published in Aethiopica 22 (2019).

[ii] Jeremy R. Brown and Daria Elagina, A New Witness to the Chronicle of John of Nikiu: EMML 7919, Aethiopica 21 (2018), pp. 120-136.

KIND REQUEST FROM ON COPTIC NATIONALISM JOURNAL TO ITS READERS

The Journal of On Coptic Nationalism would like to kindly ask readers, if they approve of what we write, to like it and help in spreading the word by sharing.

With many thanks and kind regards.

Dioscorus Boles

COPTIC RELATIONS WITH ROME 1: PURCHAS’ ACCOUNT

Samuel Purchas (c.1577 – 1626) was an English clergyman who was geographic editor and compiler of reports by travellers to foreign countries.[i] In 1625, he published the encyclopaedic Hakluytus posthumus, or, Purchas his Pilgrimes in four volumes.[ii] In 1905, J. MacLehose and sons reprinted the work in several volumes in Glasgow.

Purchas speaks aboutthe Copts, whom he calls “Cophti”, at several pages of his work. One of the relevant passages is the one titled Of the Cophti, their synode at Cairo, the Jesuits being the Popes Agents (pp. 415-416). I reproduce this passage below:

Pope Gregorie the Thirteenth sent divers messages to the Cophti, whereby a Synod was procured at Cairo, in December 1582, which had three Sessions to reconcile them to the Roman Church. At the first were present Bishops and principall men. At the third, the same men, with the Jesuites, especially John Baptista Romanus. In the first were opened the causes of their decession in the Conventicle of Ephesus assembled by Dioscorus, whereby Eutyches his Heresie which denied two natures in Christ was begun, condemned after in the Chalcedon Councell. They desired to search their Writings which were few and eaten with Age. And in the second Session was much alteration, and the matter put off to the third. In that third the Law of Circumcision was abrogated first; and after that Anathema was denounced against such as should spoile Christ of either. Yet for all this the Vicar of the Patriarke then being, resisted the subscribing, and a quarrell was picked by the Turkes against the Popes Agents, as if they sought to subject the East, to the Pope, or the King of Spaine. They were therefore cast into Prison, and their redemption cost 5000. Crownes.

At Cairo is a Librarie in which are kept many Bookes of the ancient Doctors in Arabike, as of Saint Jerome, Gregorie Nazianzene, Saint Basil, &c. and the men have good wits, and some thereby proove learned. In the time of Pope Clement the Eighth, Marke the Patriarke sent a Submission to the Pope, as was pretended; but it prooved to be the Imposture of one Barton.[iii]

Relevant to this account, he speaks in his passage Of the Egyptian Cophti. Rites and opinions of the Cophti, or Egyptian Christians (pp. 369-375) about the beliefs of the Copts, and an embassy from Patriarch Mark V (1603 – 1609) to Pope Clement VIII (1592 – 1605), wherein Mark V is said to have submitted and reconciled himself and the Provinces of Egypt to the Pope:

15. Repute the Roman Church hereticall, and avoid the communion and conversation of the Latines, no lesse then of Jewes. And although Baron, in fin. Tom. 6, Anal, have registred an Ambassage from Marcus the Patriarch of Alexandria to Pope Clement the Eighth, wherein hee is said to have submitted and reconciled himselfe and the Provinces of Egypt to the Pope, yet the matter being after examined was found to bee but a tricke of Imposture, as Th. a Jes.1.7.p.i.c.6. hath recorded.[iv]

These passages are important, at least in what they tell us about the Coptic relations with Rome to reunify the two churches. Consultations between Rome and Alexandria to reunify the Coptic Orthodox Church with the Roman Catholic Church did not start by the episodes Purchas mentions, and they did not end with them. The history of these discussions is long. I will use Purchas as a springboard to talk about this important subject in a series of short articles.

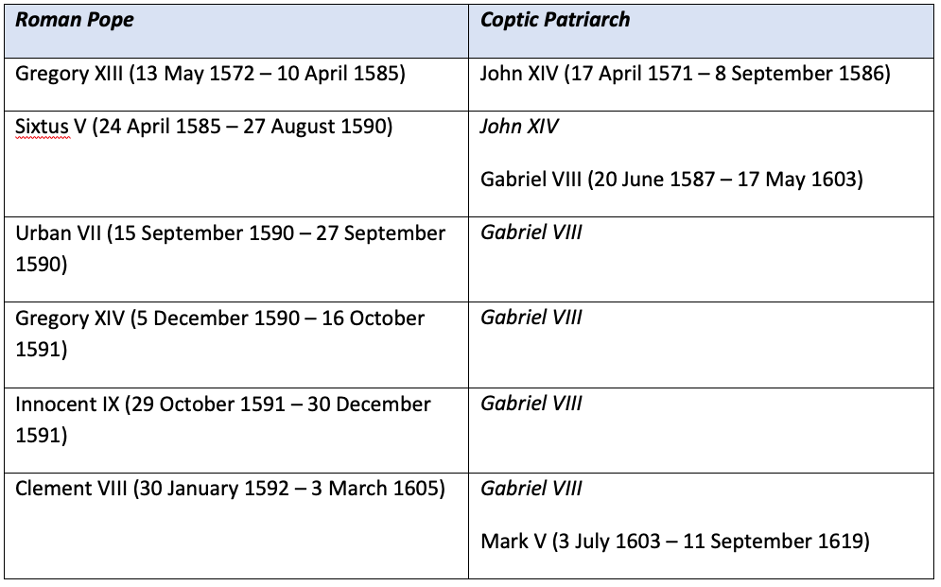

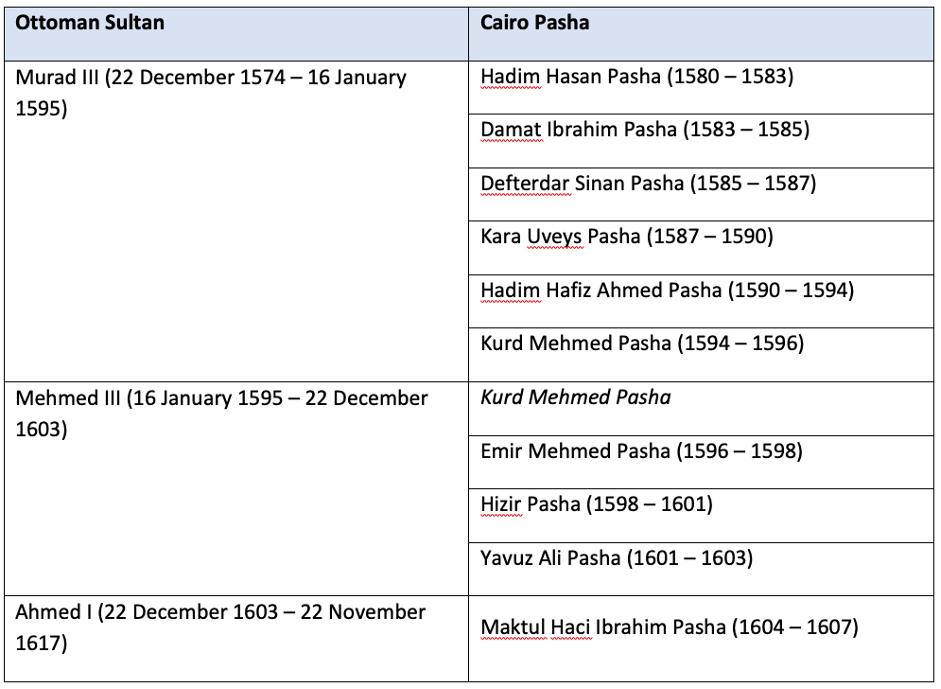

At this stage, I will just list here the Roman popes and Coptic patriarchs who preside over their relative churches at the time covered by Purchas:

The Copts were then subjects of the Ottoman Empire (since 1517) with the Ottoman sultan residing in Constantinople while the governorship of Egypt was maintained by a pasha.

[i] He, himself, was not a traveller.

[ii] Full title of the work, Haklvytvs posthumus, or, Pvrchas his Pilgrimes. Contayning a history of the world, in sea voyages, & lande-trauells, by Englishmen and others … Some left written by Mr. Hakluyt at his death, more since added, his also perused, & perfected. All examined, abreuiated, illustrates w[i]th notes, enlarged w[i]th discourses, adorned w[i]th pictures, and expressed in mapps. In fower parts, each containing fiue bookes. [Compiled] by Samvel Pvrchas. The reader can access the four volumes at Global Gateway, here.

[iii] Ibid, pp. 415-6.

[iv] Ibid, p. 371.

EVEN THE LORD’S PRAYER IS MESSED UP WHEN THE COPTIC PARTICLE “Ϫⲉ” IS MISUNDERSTOOD!

It’s a tell-tale of the current sorry state of Coptic is the way Copts recite the Lord’s Prayer in churches and outside them. The Lord’s Prayer is wrongly called in Coptic circles ‘je pen iowt” (ϫⲉ ⲡⲉⲛ ⲓⲱⲧ). The presence of je (ϫⲉ) here is curious. The way the Copts say the Lord’s Prayer is as follows:

Even when they teach their children, they use the ϫⲉ to open the prayer, as the following video by the Banha Choir of the Angels demonstrates:

It seems that we have taken the Lord’s Prayer to start with ϫⲉ, hence we say: Ϫⲉ ⲡⲉⲛⲓⲱⲧ.

Now, the Lord’s Prayer is found in the Gospels in both the Gospel according to Matthew (6: 9-13) and the Gospel according to Luke (11: 2-4). The beginning in Mathew’s, and its translation, is as follows:

(9) ⲧⲱⲃϩ ⲟⲩⲛ ⲛ̀ⲑⲱⲧⲉⲛ ⲙ̀ⲡⲁⲓⲣⲏϯ ⲡⲉⲛⲓⲱⲧ ⲉⲧϧⲉⲛ ⲛⲓⲫⲏⲟⲩⲓ ⲙⲁⲣⲉϥⲧⲟⲩⲃⲟ ⲛ̀ϫⲉ ⲡⲉⲕⲣⲁⲛ

(9) Pray ye then thus. Our Father who art in the heavens, hallowed be thy name.

The beginning, and translation, in Luke is as follows:

(2) ⲡⲉϫⲁϥ ⲇⲉ ⲛⲱⲟⲩ ϫⲉ ϩⲟⲧⲁⲛ ⲁⲣⲉⲧⲉⲛϣⲁⲛⲉⲣⲡⲣⲟⲥⲉⲩⲭⲉⲥⲑⲉ ⲁϫⲟⲥ ⲡⲉⲛⲓⲱⲧ ⲉⲧϧⲉⲛ ⲛⲓⲫⲏⲟⲩⲓ ⲙⲁⲣⲉϥⲧⲟⲩⲃⲟ ⲛ̀ϫⲉ ⲡⲉⲕⲣⲁⲛ ⲙⲁⲣⲉⲥⲓ̀ ⲛ̀ϫⲉ ⲧⲉⲕⲙⲉⲧⲟⲩⲣⲟ ⲡⲉⲧⲉϩⲛⲁⲕ ⲙⲁⲣⲉϥϣⲱⲡⲓ ⲙ̀ⲫⲣⲏϯ ϧⲉⲛ ⲧⲫⲉ ⲛⲉⲙ ϩⲓϫⲉⲛ ⲡⲓⲕⲁϩⲓ

(2) And he said to them: When ye should pray, say: Our Father who art in the heavens, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done, as in (the) heaven, so upon the earth.

As you can see, in both Matthew and Luke, the prayer starts with “ⲡⲉⲛⲓⲱⲧ ⲉⲧϧⲉⲛ ⲛⲓⲫⲏⲟⲩⲓ” (Our Father who art in heaven). There is no ϫⲉ being used before the actual words of the prayer. Ϫⲉ is used in Coptic to denote several meanings, but is usually used as a particle following verbs of speaking, naming or calling. It is used before direct or indirect speech or question to alert the reader or the listener that what comes next is a speech or question, direct or indirect. It does not constitute part of the speech or question itself. But as we have seen, in both Matthew’s and Luke’s, the prayer itself is not preceded by ϫⲉ.

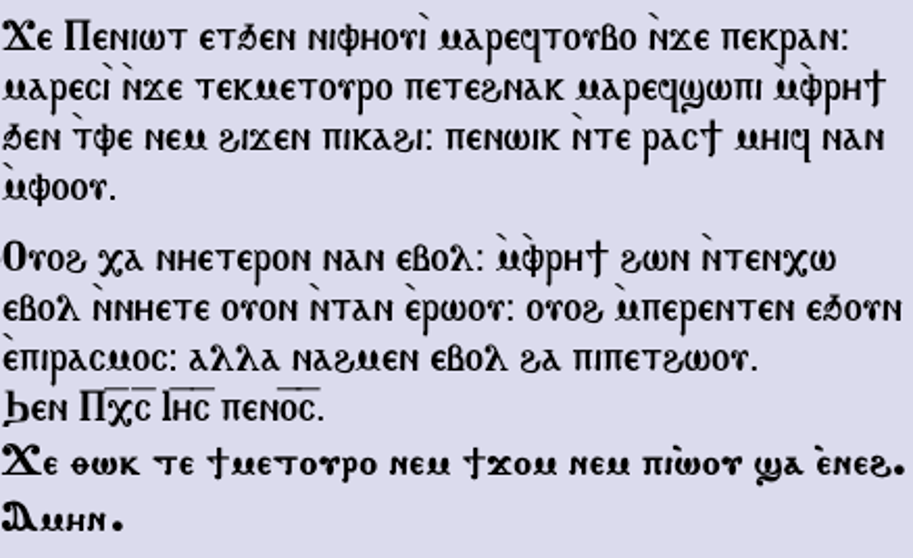

Where could have this tagging of the beginning of the Lord’s Prayer by ϫⲉ could have come from? I believe it is what Copts, who have forgotten their national tongue, listen to in the Liturgy being said at the end of the Prayer of the Fraction. Here, the priest ends his long prayer, and says:

Purify our souls, our bodies, our spirits, our hearts, our eyes, our understanding, our thoughts and our consciences, so that with a pure heart, an enlightened soul, an unashamed face, a faith unfeigned, a perfect love, and firm hope, we may dare with boldness without fear to pray to You, O God the Holy Father Who are in the heavens and say: Our Father…

And the congregation recites with him the Lord’s Prayer.

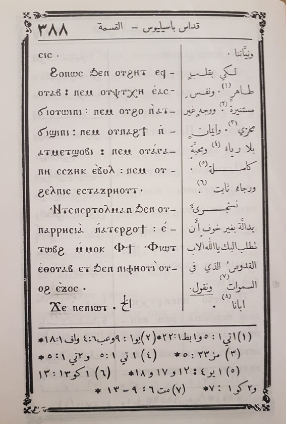

When said in English or Arabic, it doesn’t give rise to confusion, but when it is said (or read) in Coptic, confusion arises. I copy below the Coptic (with parallel Arabic) equivalent from the Holy Kholagi:

The confusion, in my opinion, arises from a poor understanding of the function or meaning of the article ϫⲉ, coupled with the situation of the poorly developed punctuation in Coptic. Ϫⲉ as we can clearly see, is attached to the first word in the Lord’s Prayer, ⲡⲉⲛⲓⲱⲧ, and therefore the prayer seems to start with “Ϫⲉ ⲡⲉⲛⲓⲱⲧ”. This is inevitable when ϫⲉ is separated from its previous syntax with a full stop.

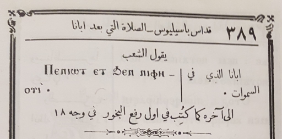

We can see this also in other prayers, when the priest says: “Makes us worthy to say with thanks, Our Father …”, and the congregation follows him in reciting the Lord’s Prayer. Here is a copy of one of the prayer books, and again it demonstrates the same mistake:

It should, of course, have been:

Ⲁ̀ⲣⲓⲧⲉⲛ ⲛ̀ⲉⲙⲡ̀ϣ ⲁⲁ̀ϫⲟⲥ ϧⲉⲛ ⲟⲩϣⲉⲡϩ̀ⲙⲟⲧ ϫⲉ: Ⲡⲉⲛⲓⲱⲧ ⲉⲧϧⲉⲛ ⲛⲓⲫⲏⲟⲩⲓ̀ …

Such an error with the function of ϫⲉ is witnessed in all Coptic documents in our modern age, particularly in the Bible. In the Bible, one verse will be specified to the introduction to the direct speech or question, while the next one will be specified to the speech or question itself. They way verses are divided in the Coptic Bible is often confused, and the ϫⲉ particle is included with the second verse, giving the impression that it is part of the speech or question. I take verses 1, 2 and 7,8 in Matthew 15 as an example:

(1) ⲧⲟⲧⲉ ⲁⲩⲓ̀ ϩⲁ ⲓⲏ̅ⲥ̅ ⲉ̀ⲃⲟⲗ ϧⲉⲛ ⲓⲗ̅ⲏ̅ⲙ̅ ⲛ̀ϫⲉ ϩⲁⲛⲫⲁⲣⲓⲥⲉⲟⲥ ⲛⲉⲙ ϩⲁⲛⲥⲁϧ ⲉⲩϫⲱ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟⲥ

(2) ϫⲉ ⲉⲑⲃⲉⲟⲩ ⲛⲉⲕⲙⲁⲑⲏⲧⲏⲥ ⲥⲉⲉⲣⲡⲁⲣⲁⲃⲉⲛⲓⲛ ⲛ̀ⲛⲓⲡⲁⲣⲁⲇⲟⲥⲓⲥ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲛⲓⲡⲣⲉⲥⲃⲩⲧⲉⲣⲟⲥ ⲛ̀ⲥⲉⲓⲱⲓ ⲅⲁⲣ ⲛ̀ⲛⲟⲩϫⲓϫ ⲉ̀ⲃⲟⲗ ⲁⲛ ⲉⲩⲛⲁⲟⲩⲉⲙ ⲱⲓⲕ

(1) Then came to Jesus from Jerusalem Pharisees and scribes, saying:

(2) Wherefore do thy disciples transgress the traditions of the elders? for they wash not their hands, being about to eat bread.’

(7) ⲛⲓϣⲟⲃⲓ ⲕⲁⲗⲱⲥ ⲁϥⲉⲣⲡⲣⲟⲫⲏⲧⲉⲩⲓⲛ ϧⲁⲣⲱⲧⲉⲛ ⲛ̀ϫⲉ ⲏⲥⲁⲓⲁⲥ ⲡⲓⲡⲣⲟⲫⲏⲧⲏⲥ ⲉϥϫⲱ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟⲥ

(8) ϫⲉ ⲡⲁⲓⲗⲁⲟⲥ ⲉⲣⲧⲓⲙⲁⲛ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟⲓ ϧⲉⲛ ⲛⲟⲩⲥⲫⲟⲧⲟⲩ ⲡⲟⲩϩⲏⲧ ⲇⲉ ⲟⲩⲏⲟⲩ ⲥⲁⲃⲟⲗ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟⲓ

(7) [The] hypocrites, well prophesied about you Esaias the prophet, saying:”

(8) This people honoureth me with their lips, but their heart (is) far away from me.

With right punctuation and proper understanding of the particle ϫⲉ, the verses above would be rendered as follows:

(1) Ⲧⲟⲧⲉ ⲁⲩⲓ̀ ϩⲁ ⲓⲏ̅ⲥ̅ ⲉ̀ⲃⲟⲗ ϧⲉⲛ ⲓⲗ̅ⲏ̅ⲙ̅, ⲛ̀ϫⲉ ϩⲁⲛⲫⲁⲣⲓⲥⲉⲟⲥ ⲛⲉⲙ ϩⲁⲛⲥⲁϧ, ⲉⲩϫⲱ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟⲥ ϫⲉ:

(2) Ⲉⲑⲃⲉⲟⲩ ⲛⲉⲕⲙⲁⲑⲏⲧⲏⲥ ⲥⲉⲉⲣⲡⲁⲣⲁⲃⲉⲛⲓⲛ ⲛ̀ⲛⲓⲡⲁⲣⲁⲇⲟⲥⲓⲥ ⲛ̀ⲧⲉ ⲛⲓⲡⲣⲉⲥⲃⲩⲧⲉⲣⲟⲥ? Ⲛ’ⲥⲉⲓⲱⲓ ⲅⲁⲣ ⲛ̀ⲛⲟⲩϫⲓϫ ⲉ̀ⲃⲟⲗ ⲁⲛ, ⲉⲩⲛⲁⲟⲩⲉⲙ ⲱⲓⲕ.

(7) Ⲛⲓϣⲟⲃⲓ, ⲕⲁⲗⲱⲥ ⲁϥⲉⲣⲡⲣⲟⲫⲏⲧⲉⲩⲓⲛ ϧⲁⲣⲱⲧⲉⲛ, ⲛ̀ϫⲉ ⲏⲥⲁⲓⲁⲥ ⲡⲓⲡⲣⲟⲫⲏⲧⲏⲥ, ⲉϥϫⲱ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟⲥ:

(8) Ⲡⲁⲓⲗⲁⲟⲥ ⲉⲣⲧⲓⲙⲁⲛ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟⲓ ϧⲉⲛ ⲛⲟⲩⲥⲫⲟⲧⲟⲩ̄; ⲡⲟⲩϩⲏⲧ ⲇⲉ ⲟⲩⲏⲟⲩ ⲥⲁⲃⲟⲗ ⲙ̀ⲙⲟⲓ.

PAXAMATIA – The STABLE FOOD ITEM AND MAIN CALORIE PROVIDER OF THE FATHERS OF THE DESERTS

The staple food of the Fathers of the Desert, and their main energy provision, as revealed in the Apophthegmata Patrum (Sayings of the Desert Fathers) was the paxamatia as the word is given in the Greek version. In the original Coptic version, it is simply called ‘oik’, which stands for bread in Coptic.

What is this paxamatia? And how was it eaten? Benjamin Hansen explains:

Paxamatia, a small loaf, about twelve ounces in weight, made of wheat, barley, or even chickpeas. Baked in bulk and distributed by basket, the bread was intentionally dry. A monk could store this bread for weeks or even months and would reconstitute it by dipping the loaf into water.[1]

Lucien Regnault gives the weight of the paxamatia as half given by Hansen and explains further:

From time immemorial, as today, bread is the Egyptian’s essential food. It seems that Egypt is actually the country where the average consummation of bread per capita is the highest. With the Desert Fathers, bread was the main food, often the only one. … These were the small, round, thick loaves that are still baked in Upper Egypt and in the Coptic monasteries – loaves which can be dried and kept for months. Before eating them, one soaks them in water. They are about four and three-quarters inches in diameter and weigh a bit more than six ounces. Two loaves weigh approximately twelve ounces, that is, one Roman pound (about forty grams). Palladius[2] speaks about these six-ounce loaves. …

In Cassian’s times,[3] two loaves made up the daily ration for most anchorites. They ate one at the ninth hour and kept the other to share eventually with a visitor. The monk who had not received a visitor ate the second loaf at night. But some contented themselves with one loaf a day; they took two only when they hadn’t eaten the night before. …

In Scetis, as everywhere else, one would normally add salt to the bread. Paphnutius declared that bread without salt made one sick. Bread and salt were also on the normal menu for Pachomian ascetics. …

Some monks purchased their bread by trading baskets or mats in exchange. They kept their bread supplies in a special hutch or basket. Like Antony, Aresenius had enough for several months or even a year. In Nitria, then in Scetis, when the number of monks increased, they set up bakeries where each one came to make his bread.[4]

To compare the quantity of bread an ascetic ate, one has to compare the one or two loaves (as sized by Regnault) with what the fellah in modern Egypt eats: an average of a dozen loaves a day, over three pounds.[5]

The diet of a Coptic monk, Hansen tells us, was in most respects quite similar to that of a given Egyptian peasant: bread and salt, of course, and a stew of lentils or porridge of grain.[6] This statement is correct for as long as the portion is taken out of it. It is interesting that the staple food item of the modern Egyptian man, fûl (stew of cooked fava beans), does not appear in the diet of the Egyptian monks. I guess foul was introduced into Egypt late, but that needs another study.

At the end, it may be interesting to mention that the paxamatia has retained its name in modern Greece as it denotes the traditional Greek cookie or biscotti. It is still made of wheat, barley or chickpeas, and it is still eaten dry, but the shape, size and weight differ from that we see in the Sayings of the Fathers of the Desert. The reader can read about it here.

[1] Benjamin Hansen, Bread in the Desert: The Politics and Practicalities of Food in Early Egyptian Monasticism. Church History (2021), 90, 286-303.

[2] Palladius of Antioch, d. 390.

[3] John Cassian, d. 435.

[4] Lucien Regnault, The Day-to-Day Life of the Desert Fathers in Fourth-Century Egypt , tr. Étienne

Poirier, Jr (St. Bede’s Publications, Petersham, Massachusetts, 1998), pp. 65-69.

[5] Ibid, p. 66.

[6] Ibid, p. 67.

WINE IN COPTIC CULTURE, NOW AND THEN

In modern times, we have been bombarded by strict ecclesiastical rhetoric that wine (an alcoholic drink made from fermented grape juice) is ‘haram’. Haram is of course not a Christian expression but Islamic, and finds its root in the Quran and the Traditions of Muhammad, meaning ‘forbidden’; that is, it is a sinful act. It donates the meaning that something is absolutely forbidden and is not a matter for questioning, reviewing, or thinking. In Islam, wine, or alcohol in general, is such haram.

The attitude we find from some ecclesiastical notables is a reflection of their sensitivity towards Islam – they want to emphasise to the Muslims that Christianity is not less strict, or laxer, than Islam. The whole thing sounds like a competition between Christianity and Islam on who is more puritanical. The Muslims have always hailed criticism on the Christians that Christians are “drinkers of wine and eaters of pork”. Recently the St-Takla.org has been leading the campaign to make wine haram, using distorted logic to prove its point. Muslim press have seized on this, and a headline from Al-Dastour, an anti-Coptic paper headed by the Islamist Muhammad al-Baz, ran an article under the heading, “Orthodoxy: The Gospels prohibited wine, looking at it, and reclining with its drinkers”! Sober heads in the Coptic Church, like the late Bishop Gregorius tried to bring sense into the debate, and differentiated between halal (permitted) wine and haram wine (that leads to drunkenness).

In my view, this attitude is part of the cultural assimilation that has hit the Coptic nation since the Arab Conquest of Egypt in the seventh century, and is very dangerous, socially and theologically.

As to the fact that drinking wine is not a sin in Christianity, we don’t need more than the example of Christ: he used to drink wine (“The Son of man is come eating and drinking; and ye say, Behold a gluttonous man, and a winebibber, a friend of publicans and sinners!”),[1] and in the Wedding of Cana Christ transformed water into wine.[2] Following what He did in the Last Supper, Christians celebrate the Holy Communion with bread and wine.

This was understood by the Church from its earliest times. The canons of the Church abide by precautions to the Christians from considering drinking wine, eating meat, or marrying as sin – three of the things which false religiosity in the past, and still in the present, is obsessed with. One can see that in the Canons of St. Athanasius.[3] The canons denounce those who drink wine in excess (that is, becoming drunk).[4] No deacon or any of the clergy should drink in the holy places. No cleric should drink wine in the day time, except one or two glasses. And if they drink, they should not get out of the city, so as they don’t bring shame to the image of Christ.[5] No cleric should drink wine at all in the Pascha (Passion Week).[6] And those who would like to become virgins, no nun should drink wine at all, and same to the monk – those who would like to keep the vow of virginity. And if an ascetic fell ill, he should drink a little bit of wine.[7] It is clear that St. Athanasius makes distinction between drinking wine and drinking wine to the extent of getting drunk. Ascetics, who have chosen to stay virgin, ought not to drink wine. The clergy who can drink wine, have to avoid drinking wine in consecrated places, and not exceed two glasses.

This understanding that drunkenness is a sin but drinking wine in moderation is not a sin continued in the Coptic Church in the Middle Ages. Patriarch Gabriel ibn Turayk (1131 – 1145) in his Nomocanon stresses the sinfulness of drunkenness, and says:[8]

Don’t get drunk with wine, and go out in the streets when you are not at work, and misbehave. (He cites the Didascalia Apostolorum here.)

If any man that is called a brother be a fornicator, or covetous, or an idolater, or a railer, or a drunkard, or an extortioner; with such an one no not to befriend or to eat. (Quoting St. Paul.)[9]

Do not be drunk with wine, in which there is no salvation. (Quoting St. Paul, again.)[10]

However, wine is not impure, and drinking it in moderation is not to be spurned. Quoting Pope Clement I of Rome (88 – 99), the Nomocanon says:[11]

Any bishop or priest or deacon – or any one of the clergy – if they abstained from marrying, or eating meat, or drinking wine, not for the sake asceticism, but because they consider them impure, should be reprimanded. And if they don’t change their views, they should be excommunicated.

If a bishop or priest or deacon does not eat some meat and drink some wine in the feasts [of the Church], and their conscience prohibits it, sowing doubts within some, they should be excommunicated.

Lest some think these canons pertain to the clergy only, we have in Chapter 11 of the Canons of Ibn al-Assal, known as “al-majmo’a al- alṣafawi”, from the thirteenth century advice given to the laity and the faithful in general. Drunkenness is certainly shunned upon, and the faithful should not drink in taverns, but in their homes. Wine is not impure, neither is drinking it is sinful, but the canon says plainly: “Eat and drink in moderation, and do not get drunk so that people make of you laughing stocks.”[12]

Our martyrs drank wine too. The reader can find plenty of examples of that – during the Great Persecution at the times of Diocletian and Galerius in the early forth century, and as Christians were hurled into prisons across Egypt, being tortured and awaiting execution, the brethren used to visit them, taking with them food, wine and oil for their entertainment. We see this clearly in the Martyrdom of SS. Paese and Thecla, for example. When Diocletian issued his notorious edict on 28 February 303 AD, “many of the Christians offered their bodies to death and fire and sword and divers manners of death; and the prisons were filled in each place with men and women for the sake of the name of Christ. And the letters were brought south to the Thebaid and were given to the governor Eutychianus, and he persecuted the Christians. And great numbers were cast into the prisons in each place. And Paese the man of Pousire would arise, and go into Shmoun and Antinoou, and cook great meals, and prepare wine, and load it upon his labourers and servants, and journey and go to the prisons, and urge the saints to eat his repast. And the saints would see a shining crown hovering over his head, and they knew that he too was a saint like themselves; wherefore they would partake of his repast, and eat.”[13] Paese’s sister, Thecla, who lived in Antinoou, was widowed when young, “[a]nd many rich men of the city urged her saying, ‘We wish to take thee to wife’; but she was not persuaded, but resolutely devoted herself to the saints, binding up their wounds; to their bodies, subjected to tortures, she applied oil and wine.”[14]

When Paul, Paese’s friend went to Alexandria and fell ill, he sent to Paese asking him to join so that he may see him for the last time. Paese goes to Alexandria, but finds that Paul had recovered. While in Alexandria, he dedicated himself to visiting the saints in the city’s prisons. He went to Paul, “and he said to him: ‘I desire, my brother, that thou do this little thing for me.’ Paul said to him, ‘Tell me what thou wilt, and I will do it for thee.’ Paese said to him, ‘I wish that thy servants go with me, since I am a stranger in this city, that I may buy a little wine and some few articles of food, and let them cook it for me, that I may load them with it, and they may come with me to the prison, so that I may eat with the saints before I come home to the south.’ And Paul was very glad when he heard this. He gave orders to his servants, and they went straightaway and bought everything which he ordered them. And Paese made a great expenditure upon bread and wine and oil, as much as a hundred articles of food; he himself bought them, and when the servants of Paul had cooked the food, he loaded them with it and took it into the prisons that day, and he urged the saints to eat from his hands; and Paese had his loins girt up, ministering to the saints. On the morrow again he went into another of the prisons, and he informed us concerning the imprisoned saints, and gave them to drink.”[15]

As it happened, Paese himself publicly confessed his Christianity, and he, on his turn, was cast in prison and tortured. Back in the Thebaid, his sister Thecla, not hearing from him for a time, decided to travel to Alexandria to be with him. In what may be one of the most beautiful pieces of Coptic literature, the writer of the Martyrdom tells us how Thecla came upon the quay of Antinoou, and found a little ship in which were the angels, Raphael and Gabriel, whom she thought were sailors, and in the prow of the ship sat St. Mary, the Holy Virgin, and Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist, whom she thought were gentlewomen from the province.

And the angels put all her baggage on board, and she embarked with one servant-woman of hers only. The angels put the ship out, and set sail northwards, for the south wind was blowing. And Thecla thought that the angels were sailors; and she said to them, ‘My brethren, take a little wine for yourselves, and a few pieces of bread, and a little fish, and eat, because you have taken trouble with me.’ But they said to her, ‘What thou thyself carest to give with thine hands, give it to us; for we will not touch any of thy baggage, lest thou say, ‘These men have undone my baggage.’ And Thecla bade her serving-maid give them what they needed – for she thought that they were men in the flesh.[16]

As the ship was sailing north, interesting conversation went on between the two ladies and Thecla about who they were and why they were going to Alexandria. Eventually, Raphael told her that he knew that she was Thecla, the daughter of Elias.

And the ladies embraced Thecla, and kissed her mouth and her head; and they said to her, ‘If thou art the sister of Paese, we rejoice with thee.’ She arose forthwith, and made ready a table, and she laid upon it many dainties, and wine; for she thought that they were people in the flesh. And Thecla was attending and ministering to them; for they appeared as if eating.[17]

Coptic hospitality and generosity in those days were great, and bread, wine and oil formed fundamental ingredients of them.

The Fathers of the Desert, in their strict asceticism and austerity of diet, were keen not to make wine-drinking be considered a sin. Some saints did not think wine is compatible with the ascetic life. Abba Poemen was once asked about a monk who drank wine, and he answered: “Wine is not for monks.”[18] This strict abstention from wine was not a general rule, though, and drinking one or two glasses of wine was accepted. Three glasses of wine were, however, considered excessive wine drinking. I quote Benjamin Hansen in his excellent review of eating and drinking by the Fathers of the Desert:

… Abraham, the disciple of Abba Sisoes, asked him: “If the gathering takes place on Saturday or Sunday and a brother drinks three cups of wine, is that not a lot? The old man said, “If Satan is not in it, it is not much.” It is hard to take this Sisoes at his word: elsewhere in the Alphabetical Collection, we find him on a mountaintop with his fellow monks and a bottle of wine. Sisoes gladly received the first cup. His companion poured him a second cup – and he drank this. His companion began to pour a third, but Sisoes stopped him. “Don’t you know,” he asked, “that a third cup is from Satan?”

Another elder, however, told his disciples that they could indeed drink up to three cups of wine “if it is unavoidable.”

Was three the limit? An anonymous elder said, “Let not a monk who drinks more than three cups of wine pray for me.

Abba Xoius made his contribution to this numerical calculation. A brother asked him a question, saying, “If I drink three cups of wine, is that a lot? Xoios answered, “If the devil did not exist, it would not be a lot. But since he exists, it is a lot.”[19]

St. Anthony the Great never drank wine, confirming the axiom of St. Poemen; but St. Macarius the Great drank it with his brothers as part of the agape when the brothers gathered in the banquet which preceded the Eucharist on Saturday and Sunday, until the day he found out that an elder would then deprive himself as many glasses of water as he had drunk of wine. He then stopped offering him any. It was therefore not an absolute rule to drink wine during a meal taken in common.[20]

A third cup is from Satan was the axiom, but not always. Monastics followed their judgement for as long as they didn’t get drunk. Other monastics drank three cups of wine. The History of the Coptic Church tells us of a story in which a Coptic Patriarch certainly drank three cups of wine. This we find in a personal encounter by one of the writers of the History, Yuhanna ibn al-Quilzami, with Patriarch Kyrillos (Cyril II). We read his account:

I went to him [Kyrillos] in the Church of Michael the Elect, on Sunday, to receive a blessing from him and to communicate in it, and I found that he had already come down from the keep and was sitting in the church. I greeted him and I received his blessing. He rejoiced in me and blessed me and honoured me, and it was that God granted to me the blessing of his prayers. He was a saintly monk, spiritual, lowly, meek, very ascetic, a hater of possessions, and giving alms of all that was brought to him from the Sees [of various bishoprics], to the weak, and spending part of it on the building of churches and monasteries, and with part of it fashioning silver vessels for use in the holy sanctuaries, and with part of it assisting the Christians who were arrested, and redeeming them from punishment, so that, when he went to his rest, there was not found on him either a dinar or a dirham.

All his deeds were good and beautiful, and he was agreeable in speaking and of pleasant appearance, fasting continually and plentiful in prayer. He used not to eat from that which was prepared in his Cell for his disciples, anything of the dishes, except one dish which used to be presented to him in a bowl, whether of cereals or of vegetables, and he ate of it a small quantity from the evening meal to the evening meal.

I sat before him and I discoursed with him till the priests assembled and asked him, and I asked him also with an obeisance, to celebrate the Liturgy, and we all communicated from his pure hands, and he prayed in Coptic for everyone who approached the Eucharist, and he blessed them.

When he had dismissed the people, and they had gone out, I started to go out, and Peter, the chief of his disciples, came out to me, and said to me: “Our father says to you with an obeisance, ‘Sit down until I come out from the sanctuary,’ and I sat down until he came out. He said to me with an obeisance, “Come up to me, and I will discourse with you to-day, and I will entertain you.” I said: “At your service,” and I went up with him to the keep, and Abba Abraham, his scribe also, and it was after noon.

The disciples presented the repast, and I and Abba Abraham ate. They brought wine, and I declined to drink it, because it was the season of the summer, and I dislike to partake of it in the summer. Then I sat before him to discourse with him. Abba Abraham informed him that I had not drunk anything, and he blamed me on account of this. I informed him that I dislike drinking wine in the summer. He said to me: “Three glasses will not harm you.” I said: “O my master, if it is from your holy hand, it will not harm me, but it will benefit me very much.” He made a sign to the disciple, and he handed to him a glass of wine, and he blessed it, and I took it from him, and I drank it, and, in like manner, the second and the third glass.[21]

The eating and drinking session, moderately consumed, was followed by a serious discussion on theology on the Incarnation, Salvation, and various issues in Christology. The reader must have noticed that here is relaxation of the rule of two glasses, perhaps because it is now afternoon and not day.

No, drinking wine is not a sin – what is a sin is excessive wine drinking and drunkenness. How much is allowed to drink of wine? It seems that the consensus has settled on one or two, with a maximum of three, glasses. But those who want to abstain from wine were right in their own approach for as long as they didn’t consider it a sin to drink wine, or looked down on those who did.

Theologically, one is at danger of being in the wrong side of theology if he says wine is impure and drinking wine is a sin, or particularly ‘haram’. “There is nothing from without a man, that entering into him can defile him: but the things which come out of him, those are they that defile the man.”[22] Wine is as meat and marriage are not sins, but a man or woman can abstain from them if they so choose and not consider them in their heart as sins. Socially, it will work better when the faithful are treated like grown ups and spoken to as sensible men and women, with the focus on doing everything in moderation. Temperance is one of the four cardinal virtues of Ancient Antiquity and one of the Seven Virtues of the Church. It does not help to use false and distorted arguments like the ones used by St-Takla.org such as saying that the water which Christ converted into wine at the Wedding of Can was not actually wine, since it “made its drinkers sober”, and “they were able to know the difference between the good wine and the bad wine”!

Bottomline: drinking wine in moderation is ok if one chose so. Excessive drinking and drunkenness are sinful. Education of the Copts on temperance must be the goal, and not blanket prohibition. The danger of making wine-drinking sinful is that it creates all the evils that the Church in the first instance tried to avoid by advocating sensible drinking by those who are not practising a certain type of asceticism.

[1] Luke 7: 34 (KJV). Also in Matthew 11: 19.

[2] John 2: 1-11.

[3] See: The Canons of Pope Athanasius, Patriarch of Alexandria, ed. Athanasius al-Maqari (Cairo, 2003).

[4] Canon 7.

[5] Canon 29.

[6] Canon 30.

[7] Canons 92 and 98. This reflects the advice given in 1 Timothy 5: 23.

[8] Canon 33.

[9] 1 Corn. 5: 11 (KJV). The Arabic text adds “with such an one not to befriend or to eat.”

[10] Ephes. 5: 18. Note the difference from the English KJV.

[11] Canon 54. The quotations are from Canons of the Apostles 2: 35, 37.

[12] See: المجموع الصفوي – كتاب القوانين الكنائسية لكنيسة الأقباط الأرثوذكسيين – الشيخ الصفي أبي الفضائل بن العسال – نشر الأستاذ جرجس فيلوثاؤس عوض – الطبعة الأولى

[13] Four Martyrdoms from the Pierpont Morgan Coptic Codices, tr. and ed. E. A. E. Reymond and J. W. B. Barns (Oxford, 1973), pp. 151-2.

[14] Ibid, p. 153.

[15] Ibid, pp. 155-6.

[16] Ibid, p. 167.

[17] Ibid, P. 168

[18] See n. 19.

[19] Benjamin Hansen, Bread in the Desert: The Politics and Practicalities of Food in Early Egyptian Monasticism. Church History (2021), 90, 286-303.

[20] Lucien Regnault, The Day-to-Day Life of the Desert Fathers in Fourth-Century Egypt , tr. Étienne

Poirier, Jr (St. Bede’s Publications, Petersham, Massachusetts, 1998), p. 76.

[21] History of the Patriarchs of the Egyptian Church, Known as the History of the Holy Church by Sawirus ibn al-Mukafa’. The Lives of Christodoulus to Michael IV (d. 1102), which were translated by Aziz Suryal Atiya, Yassa ‘Abd al-Masih & O.H.E. Burmester, and appeared in 1959 as Volume II, Part III.

[22] Mark 7: 15.

WHEN POPE SHENOUTI I TOOK THE CRUSIER IN HIS HAND AND WENT TO FACE THE MARAUDING ARABS

An important writer of the History of the Coptic Patriarchs (HCP) is a monk by the name of Yoaannis (John) II. He was the personal clerk of Patriarch Shenouti (Sanutius or Shenouda) I (858 – ?880). He wrote the fourth part of the HCP that extended from Patriarch Mina (766 – 774) to Shenouda I, nearly one hundred years of Coptic history.

He writes as a witness and close associate to the patriarchate of Shenouti, and his story of the Life of Shenouti contains valuable information. The patriarchate of Shenouti, at least its beginning, occurred in the period of the Abbasid Dynasty known as the Anarchy of Samarra (861 – 870) which witnessed bitter infighting between the sons and nephews of the Caliph al-Mutawakil (d. 861) which destabilised the Caliphate, including Egypt. And the Arab Bedouins, wo have always been a menace in Egypt, particularly when the central government is weakened, found their chance. As usual, it was the Copts who bore the brunt of the chaos and anarchy. The reader must bear in mind that at that age the Copts formed the majority of Egypt’s population.

| Caliph | Period |

| Al-Mutawakil | 847 – 861 |

| Al-Muntasir (son of al-Mutawakil and his murderer) | 861 – 862 |

| Al-Musta’een (nephew of al-Mutawakil) | 862 – 17 January 866 |

| Al-Mu’taz (brother of al-Muntasir) | 25 January 866 – 869 Yoannis II wrote his book in April 866 |

| Al-Mu’htadi (nephew of al-Mutawakil) | 869 – 870 |

Youannis II wrote his book in the year 582 AM (starts on 29 August 865 AD) and 252 AH (starts on 22 January 866 AD). We can therefore conclude that he wrote it in AD 866 in the early months of the caliphate of al-Mu’taz, when Egypt was still lurking in its Abbasid anarchy.

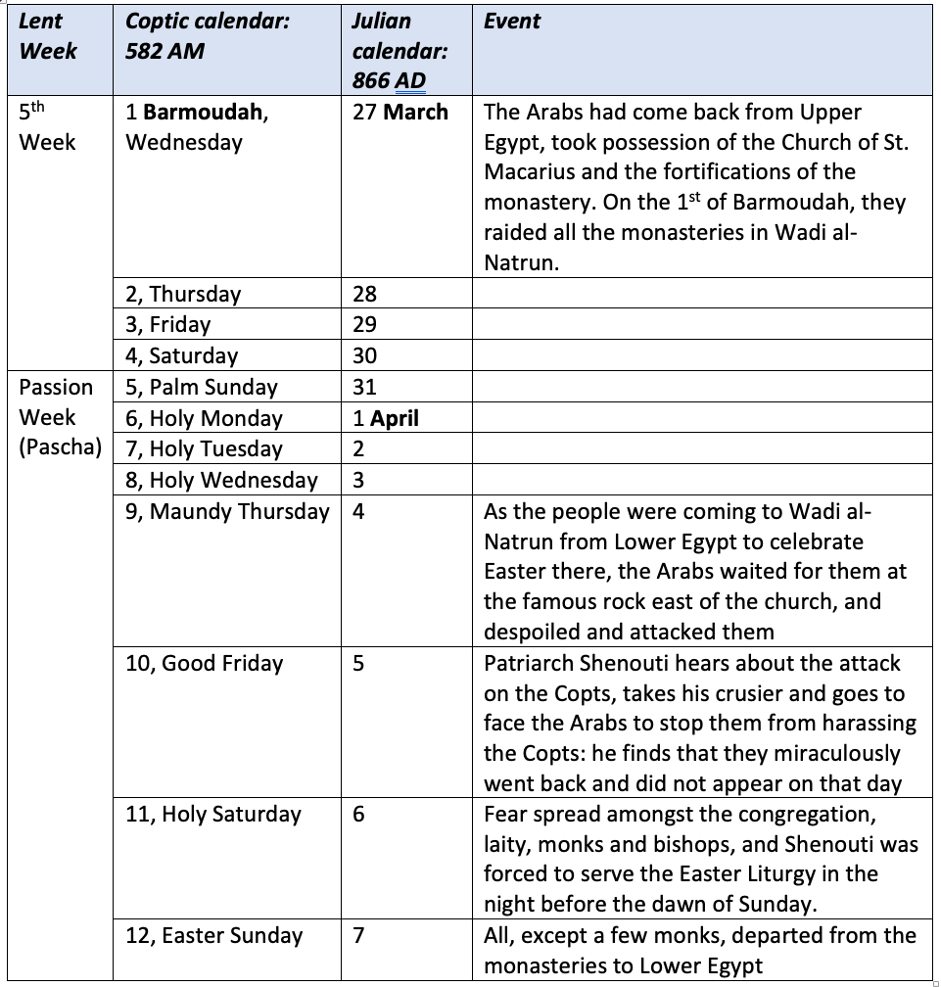

One of the incidents told by Yoannis II is what happened as he says in the eighth year of the patriarchate of Shenouti I, that is in 866. The writer does not give the year of the incident, but simply says that it happened in the Patriarch’s eighth year. Since we know for sure the beginning of Shenouti’s patriarchate, we can be sure that the incident happened in 582 AM. This incident is commemorated in the Coptic Synaxarium on 9th of Bermouda, and described as “great miracle that occurred at the hand of our father, St. Sanutius, the Patriarch”. The incident is also mentioned in the Synaxarium under the 24th of Barmouda, the day on which the death of the same patriarch is commemorated.

Below is how Yoannis II tells us the story.[1] I will divide it in sections and make comments as I go. I have provided the footnotes that the translators Yassa abd al-Masih and O. H. Burmester added, and I make my own notes too.

The chronology of these events is as follows:

Another story. It was in the eighth year of the patriarchate of this father,[2] and the days of the Holy Fast[3] drew near, and he desired to journey to the Holy Desert in the Wadi Habib[4] to accomplish there the Fast[5] and the Holy Feast of Easter. Some of the faithful counselled him not to go for fear of the marauding Arabs, for it was the time when they came down from the land of Upper Egypt[6] to the land of Lower Egypt,[7] after putting their beasts out to grass,[8] lest something should befall him through them. The saintly father said in his heart: “If I do this, I shall cause joy to Satan. If I refrain from going to the holy places, then the people will remain back because of me, and they will be deprived of the blessings of the Saints”. Then he besought the aid of God and made his way to the Wadi.

Now the Arabs knew the time when the strangers assembled there, and they arrived in secret from Upper Egypt, and they took possession of the church of the father Macarius and of the fortifications[9] and carried off all the furniture and the food and other things which were in them.

On the first day of Baramudah[10] they made the round of all the monasteries[11] and robbed all those who were in them and the people who came to them, and they drove most of them out at the point of the sword. When the father saw this affair, he was afflicted on account of it.

Then the fathers, the bishops, and the monks came together to him weeping and saying: “It was for your sake that we remained here. We desire of you that you prevent us not from departing, lest we die by the hands of this miscreant people”. This happened on the Friday of the Week of the Pascha,[12] and when our father Anba Shenouti heard of it, he knew that it was a ruse and a snare of Satan which Satan had set for him, on account of that which was in him from the Holy Spirit. He knew that he [Satan] who had assembled the people and harassed them desired thereby to devastate the desert, so that there should be none in it of them who remember the Name of God the Exalted. There upon, he said in the strength of his heart: “May the Lord strike you, O Satan and bring to nothing your conspiracy which you have formed”. The fathers, the bishops, besought him to depart, so that they might accompany him. But he said to them: “Pardon me, O my holy fathers, we will not quit this place, until we have accomplished the Feast of Easter, even if my blood is to be shed”. When the monks saw his courage and his strength of heart, they envied him for his courage, and they became strengthened and did not allow Satan to vanquish them.

The Arabs had begun[13] to harass the congregation of the monks, so that they should not accomplish the Feast of Easter, but perform the will of their father Satan. They drew their swords and stood on the rock east of the church[14] and took the clothing that they found on the people, and whosoever resisted, they wounded him with the sword. This happened on the Thursday of the Week of the Pascha,[15] the ninth of Baramudah.[16] Those of the people who escaped entered the church, crying, weeping and saying: “O our father, help us, for these Beduins have prevailed over us”.

When this saint saw the distress of the people, he rose up and took in his hand his staff on which there was the emblem of the Cross,[17] and he went out to the Arabs, saying: “It is good for me that I should die with the people of God, or, perchance, when they see me, they will refrain from their wickedness, and this weakened people will be saved”.[18]

When the bishops beheld the excellence of the intention of the father and how he delivered himself to death for his people, they took hold of him and prevented him from going out to the Arabs, and they said: “We will not let you deliver yourself into the hands of these foul murderers”. When he heard them, he said to them with humility, lowliness and strength of soul, as says Paul: “For I make known to you that this will happen to me to salvation, through your prayers and the supply of the Holy Spirit of Jesus Christ, according to my confidence and my hope… whether by life or by death. For my life is Christ and death is gain to me”.

He became strong in Christ, and he went out to the miscreant Arabs, but by the clemency of God they had gone back and they did not appear on that day, but they [Shenouti and those with him] returned by the help of God and the intention and constancy of this father Anba Shenouti, and Satan the hater of good, was put to shame.

When the faithful archon Iṣṭafan (Stephen) son of Severus whose work was good with the Lord, for he had trust in the patriarch and a love for the holy monasteries, heard this, he arose in haste and came to the monasteries and met the father and the monks and the bishops, and he strengthened their souls and put himself at their disposal, and said to the father: “I will deliver myself for you and for the people, until they have gone out from among these rebels”.

The father saw the timidity of the hearts of the people and that they were determined to go out, being terrified of the Arabs who surrounded them and desired to take them and to kill them with the edge of the sword: he strengthened them and comforted them through the grace of the Holy Spirit, and he said, as Paul said to those who were with him in the ship: “For one soul from among you shall not perish”.[19] He said to them: “God has delivered you out of the hands of these oppressors and He will fight for you”.

He perceived that some among them had little faith in what he said to them and that their hearts were timorous, so he bade them assemble all the people in the church on Sunday[20] that he might communicate them from the Holy Mysteries by night before dawn, and that he might go with them till he had brought them to Lower Egypt. Thus, their souls were strengthened. Then he arose at midnight, and the bishops and the monks and the people came together to him, and he began the Liturgy, and while he went round the sanctuary with incense, his eyes shed bitter tears, even as says Obadiah the prophet: “Let the priests that minister about the altar of the Lord weep”.[21] He wept and said as the prophet says: “Spare, O Lord, Your people, and give not Your inheritance to this reproach, that the heathen should rule over it, lest the heathen should say, Where is their God?”[22] The fathers, the monks, wept bitterly and their tears mingled with their thoughts, on account of what would befall them through the marauding Arabs, and they communicated of the Mysteries before dawn, while the Father wept over the desertion of the desert by the monks.

Then he dismissed the people, and he went out and comforted them. They blessed God and they marvelled at the strength and boldness of the father, for they saw him as Moses the prophet before the Children of Israel. Thus, by his prayers and his purity God delivered the people from the hands of the Arabs that day. But he ceased not to weep on seeing how the monks were passing over to the land of Lower Egypt for fear of the marauder, so that only a few people remained in the monasteries.

Satan did not cease to raise up trials for the churches in the land of Egypt.

This story shows the courage and strength of character of Patriarch Shenouti I. Indeed, he was called “Shephard of the Nation” by the writer. The text says, “When this saint saw the distress of the people, he rose up and took in his hand his staff on which there was the emblem of the Cross”. This is what gives this miracle a special importance. The staff on which there was the emblem of the cross cannot be but the staff of the “Bass Snakes”, the crusier (or cruzier), which symbolises Christ. It shows us that Patriarchs used to take their crusier with them wherever they went. This crusier was inherited from one patriarch to the other, and the new patriarch takes it from the altar as a sign of him getting his authority direct from Christ. The reader can read more about it here.

Was it a miracle that happened on Good Friday the 10 Barmoudah 582 AM (5 April 866 AD)? Both the History of the Patriarchs and the Coptic Synaxarium portray it as such. In the History of the Patriarch, we see in it a work of Providence: “He became strong in Christ, and he went out to the miscreant Arabs, but by the clemency of God they had gone back and they did not appear on that day”. The Arabs simply vanished or moved somewhere else following their despoiling of the Copts on Maundy Thursday. There was no actual confrontation. The Synaxarium however, which gives the date, erroneously as I think, as 9 Barmoudah (i.e., Maunday Thursday) makes it more dramatic: “And he went out to the Arabs, and the staff in his hand. And when the Arabs saw him, they retreated back, escaping, as if a great army has approached them. And they did not return from that day to do harm to the holy sites.”

The miracle is most probably as in the History of the Patriarchs: there was no confrontation, but Providence saved the Copts, and the Arabs left somewhere else. Miracle or not, I think there is another miracle in the story: the courage and strength of character of Patriarch Shenouti. Patriarch Shenouti is one of our greatest patriarchs. Patriarchs can learn a lot from his example.

[1] The story is to be found in History of the Patriarchs of the Egyptian Church, Known as the History of the Holy Church, by Sawirus ibn al-Mukaffa’, Bishop of al-Ashmunin. Volume II, Part I: Khael II – Shenouti I. Translated and annotated by Yassa abd al-Masih and O. H. Burmester (Cairo, 1943), pp. 52-56 (English translation); pp. 36-39 (Arabic section).

[2] 582 AM, equivalent to 866 AD.

[3] Lent.

[4] Scetis.

[5] Lent.

[6] The Arabs called it, Sa’id.

[7] The Arabs called Lower Egypt, Rif or Reef.

[8] Arabs used to move between Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt according to season to feed their camels and horses. They usually returned to the northern parts of Egypt in Lent months.

[9] The keeps. This occurred before the building of a wall around the Monastery of St. Macarius, an accomplishment by Shenouti I. Before the walls, the monastery was composed of scattered cells round the church, and there were keeps to which the monks hurried at events of attacks by the Berbers or Arabs.

[10] The 27th of March 866.

[11] Wadi al-Natrun had several monasteries scattered throughout it.

[12] The Passion Week that starts on Palm Sunday and ends on Easter Sunday. In that year, from 31March to 7 April 866 AD (5-12 Bermoudah 852 AM).

[13] The translators use “The Arabs began”. I changed it to “The Arabs had begun”, as it is clearly and event before Good Friday, when Patriarch Shenouti went out to challenge the Arabs.

[14] This rock is famous in Coptic history.

[15] Maundy Thursday.

[16] The 4th of April 866.

[17] This must be the crusier (or cruzier) which is also called the “Brass Serpent”.

[18] Philip. 1: 19-21.

[19] Acts 28: 22.

[20] Easter Sunday, 7th April 866.

[21] Joel 1: 9.

[22] Joel 2: 17.

AN EXCELLENT NEW EDITION OF COPTIC-ARABIC NEW TESTAMENT PUBLISHED IN EGYPT BY THE BIBLE SOCIETY OF EGYPT

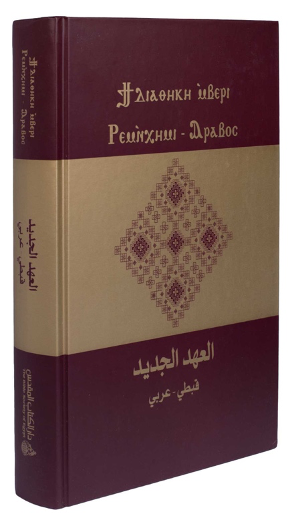

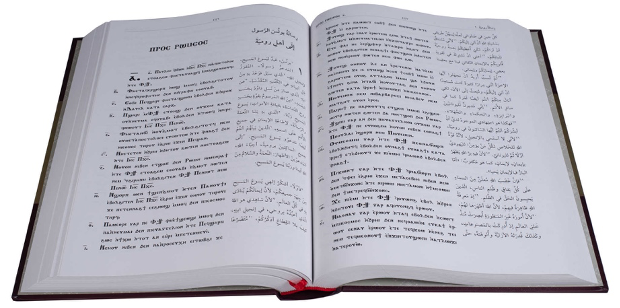

A regular correspondent (Kyrillos) has alerted me to a new publication by the Bible Society of Egypt of the New Testament in two columns: Coptic and Arabic. It is a hard cover edition, 765 pages long (with a weight of 1.7kg) and of 28.5 x 20cm page size.

I do not have a copy of this bible yet but my correspondence reassures me that he has found that it has “zero jinkim errors, zero spelling errors, correct and modern capitalisation, and proper punctuation”. IT is forwarded by Pope Tawadros II, and so it seems it has secured the blessing of the Coptic Orthodox Church.

The title of the book is “Ϯⲇⲓⲁⲑⲏⲕⲏ ⲙ̀ⲃⲉⲣⲓ Ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ – Ⲁⲣⲁⲃⲟⲥ” “العهد الجديد قبطي-عربي”. The Coptic is inaccurate, so I hope the inaccuracy is confined to the cover alone. The correct Coptic should be: Ϯⲇⲓⲁⲑⲏⲕⲏ ⲙ̀ⲃⲉⲣⲓ ϯⲙⲉⲧⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ – ϯⲙⲉⲧⲀ̀ⲣⲁⲃⲏⲥ.[1]

But the main problem of this publication is its price: it is priced at $17.76. I don’t know if that is for Copts in Egypt, or if they have a special price in Egyptian currency. No one in Egypt can buy it for that price in dollar or its equivalent in Egyptian.

For people outside Egypt, it is even worse: thus, Copts in Sudan or the UK or France or Germany have to buy it for $47.16, while those in the US have to pay $68.15!

A Coptic Bible should be available for the masses in a reasonable price that all could afford. One hopes that the Bible Society would alter its price. This publication should not be made for profit.

One hopes also that the same will be published in Coptic-English, Coptic-French, Coptic-German, etc.

[1] Or “ϯⲁ̀ⲣⲁⲃⲏⲥ”.